What’s the Cure for Fed Fatigue: Would You Believe Math?

photo credit: Unsplash

How fixed income investing can alleviate interest rate stress and how you can forecast fixed income returns.

Do you suffer from Fed Fatigue? The Federal Reserve Bank has dominated financial headlines lately. Will they, or won’t they? Do they dare drop rates? Will stubborn inflation take rates higher? It’s tiring to predict how the Fed may push or prod markets with its available tools. But there is good news, call it a tonic for Fed Fatigue. If you buy high quality core bonds, and peer out to the horizon just far enough (and that means beyond the next Federal Reserve Board meeting, and then keep going), you don’t have to worry about the Fed. Although a bit exaggerated, in truth, bonds have a powerful agent in the fight against the Fed Fatigue: Math. What once caused you headaches could actually be the cure. Let’s explore.

Stock Predictions

Previously we covered some basic ground rules for constructing a sensible approach to setting return expectations for stocks. [Link] If you enjoyed our straightforward, simple approach to forward equity returns, you’re in luck, as bonds can be even less complicated. First, we lay the groundwork for our approach by looking at the source of returns, and why (like equities) the past is not strictly prescriptive of the future. Then we’ll introduce the one simple trick for setting bond return expectations. Finally, we’ll nose our way into more nuanced corners of the market and explore the adjustments that must be considered to supplement our models.

Bond Investing 101

Distilled to its essence, bond investing is simply lending money to an entity like a country or a corporation. Bonds allow individual investors (bondholders) to assume the role of a lender. Bondholders provide cash today with an expectation of repayment of principal with interest. The terms are set when the bond is issued (but note, that does not mean there will be no surprises). Unlike equity holders, bond investors have limited upside—the best outcome is the full and timely repayment of their loan: principal plus interest. In exchange for their capped return, bond repayment will supersede any equity claims. If a borrower does not have enough cash to go around in troubled times, the bondholders take priority.

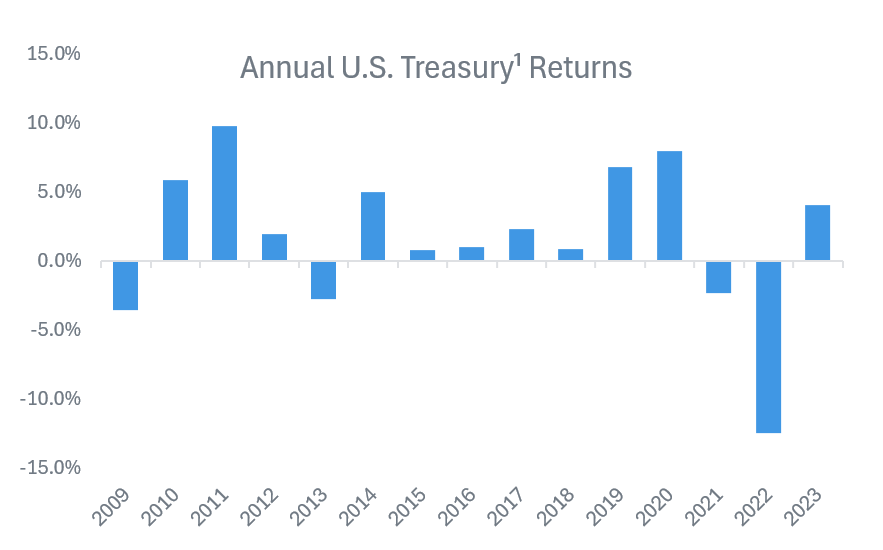

Now if bond investors can only hope to be paid back it would seem that fixed income return expectations would start at full repayment and decrease proportionately with those (hopefully rare) instances where a borrower defaults on their loan. Eyeing the annual returns earned by an investor in U.S. Treasuries will immediately challenge this approach.

Bloomberg Aggregate US Treasury Total Return Index

Source: Morningstar

For example, as you study the chart, the U.S. government wasn’t offering 8% interest in 2020, (most will remember it was close to 0%). And it certainly didn’t fail to repay its debts in 2022. Something else was driving the returns realized by Treasury investors. This is where an important aspect of fixed income markets comes into play: bondholders aren’t required to hold securities until maturity. They are free to sell those bonds to other investors throughout the life of the bond. To sell or buy securities, though, there needs to be an agreed-upon price. That price is determined by a “mark-to-market” mechanism that can drive bond return volatility an order of magnitude beyond effect of the simple repayment of money lent.

The Price Effect

Bond pricing can best be illustrated with a simple thought exercise. Suppose a borrower approaches you as an investor to lend $1M at a promised rate of interest of 6%, and further suppose that this interest rate is considered “fair” at the time the loan is originated. You agree to lend the sum at 6% interest. A year passes and the borrower’s business is humming along, and the prospects for the future are looking rosy as well. They go to another investor and secure additional funding, this time offering 5% interest. Suddenly your 6% loan looks better! If someone came along offering to purchase that loan from you, you’d want to be paid a little extra. After all, if you went to reinvest that money for a loan or bond of similar risk today, you’d only get 5% interest. In fixed income parlance, your loan would price at a premium to par, it will take more than $1M for you to part with it.

This cuts both ways, though. If instead of the outlook improving after one year, storm clouds gather, our borrower may need to offer 7% to get fresh capital. Now your promise of 6% doesn’t look so hot, and good luck getting someone to take it off your hands without offering a discount to par. Not when they can get 7% in the market with similar risk. In both instances, the size of the premium/discount will depend on how far interest rates have moved, and the duration of the loan. Being locked in at 6% for 2 years is much different than 15 years once interest rates change.

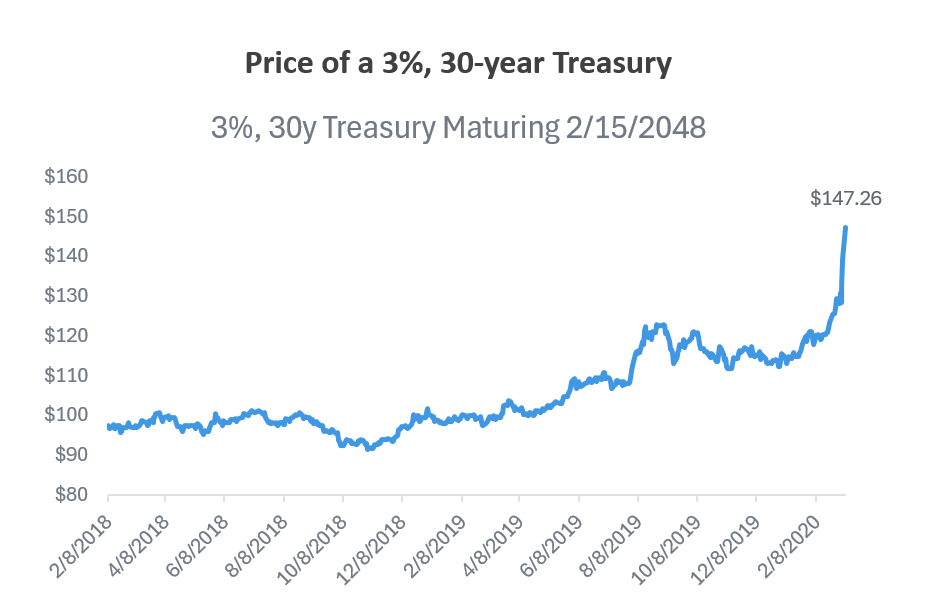

To really hammer the price effect home, we can look to the different outcomes for an investor in a 30-year U.S. Treasury at two relatively recent points in history. First, an investor buying the 30-year bond in February 2018, with a 3% coupon, saw a massive windfall during the COVID lockdown as interest rates plummeted.

Source: Bloomberg

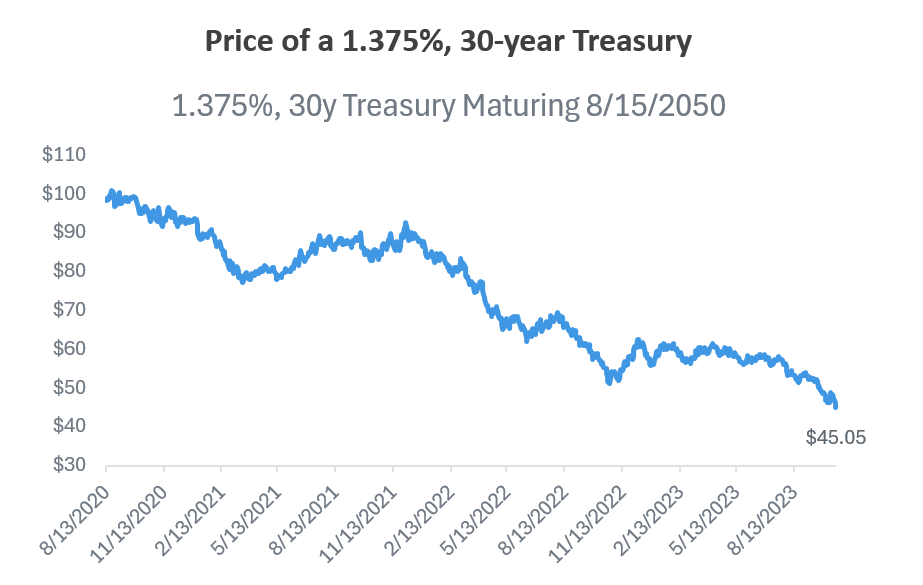

Now let’s assume a (very) naïve investor was inspired by observing such a swift and sizeable return from a “low-risk” Treasury, and decided to put this trade on for themselves, but alas, when they bought the 30-year bond in September of 2020 the coupon had dropped to 1.375%. Not long after securing this low-income position, the Fed began their fight with inflation by hiking interest rates, and our investor learned a very hard lesson on the power of duration.

Source: Bloomberg

An important distinction to make—these bonds were both issued by the U.S. Treasury; they bear the same amount of credit risk; and apart from (relatively small!) differences in their coupons and maturity dates, they are basically the same. But the pricing gulf between the two experiences exceeds the par value of the bond! Behold, the power of price return!

Yield and Investment Horizon

So, if we seek to forecast bond returns, what are we to do? Any plans we make would seem to be reliant on the future path of interest rates, which are notoriously unpredictable, and lead to Fed Fatigue. But bond math graciously offers us a reprieve in the form of yield. Yield is the effective discount rate we use to calculate the market price of a bond. And, this is different than the coupon, which, you recall, is the amount of “interest” to be paid to the bond investor/lender by the bond issuer/borrower. Yield is quoted in a variety of ways (yield to maturity, yield to call, yield to worst, etc.), but in general, if a bond is priced at a discount (or a premium) to par, the yield will be higher (or lower) than the coupon rate. If we can reinvest coupons at a rate equal to our initial yield, then our total return will be equal to the bond’s yield at the time of purchase. But why does this matter if interest rates inevitably fluctuate? This is where the magic of bond math kicks in.

The key here is the reinvestment dynamic. If a bond’s yield falls, we get a boost from the price effect, but we are reinvesting at a new lower rate. Conversely, if yields rise, we are harmed by a lower price, but we get to earn a higher return on our reinvested income. It turns out that with the appropriate investment horizon, the net effect of these moves will tend to offset each other, meaning our total return roughly matches our starting yield! How long does your investment horizon need to be for this offsetting dynamic to kick in? It depends on how long your bonds will take to mature.

Source: Bloomberg

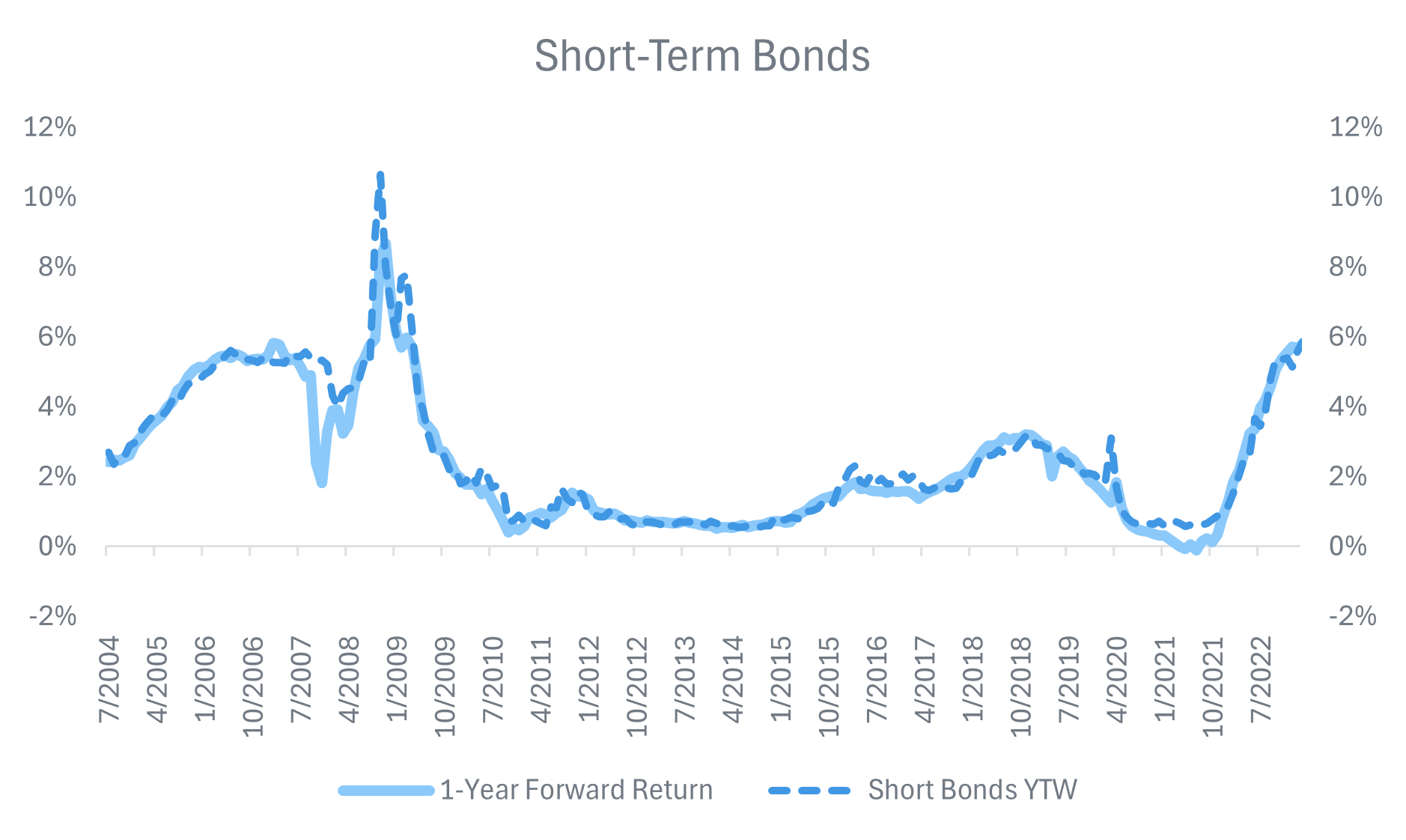

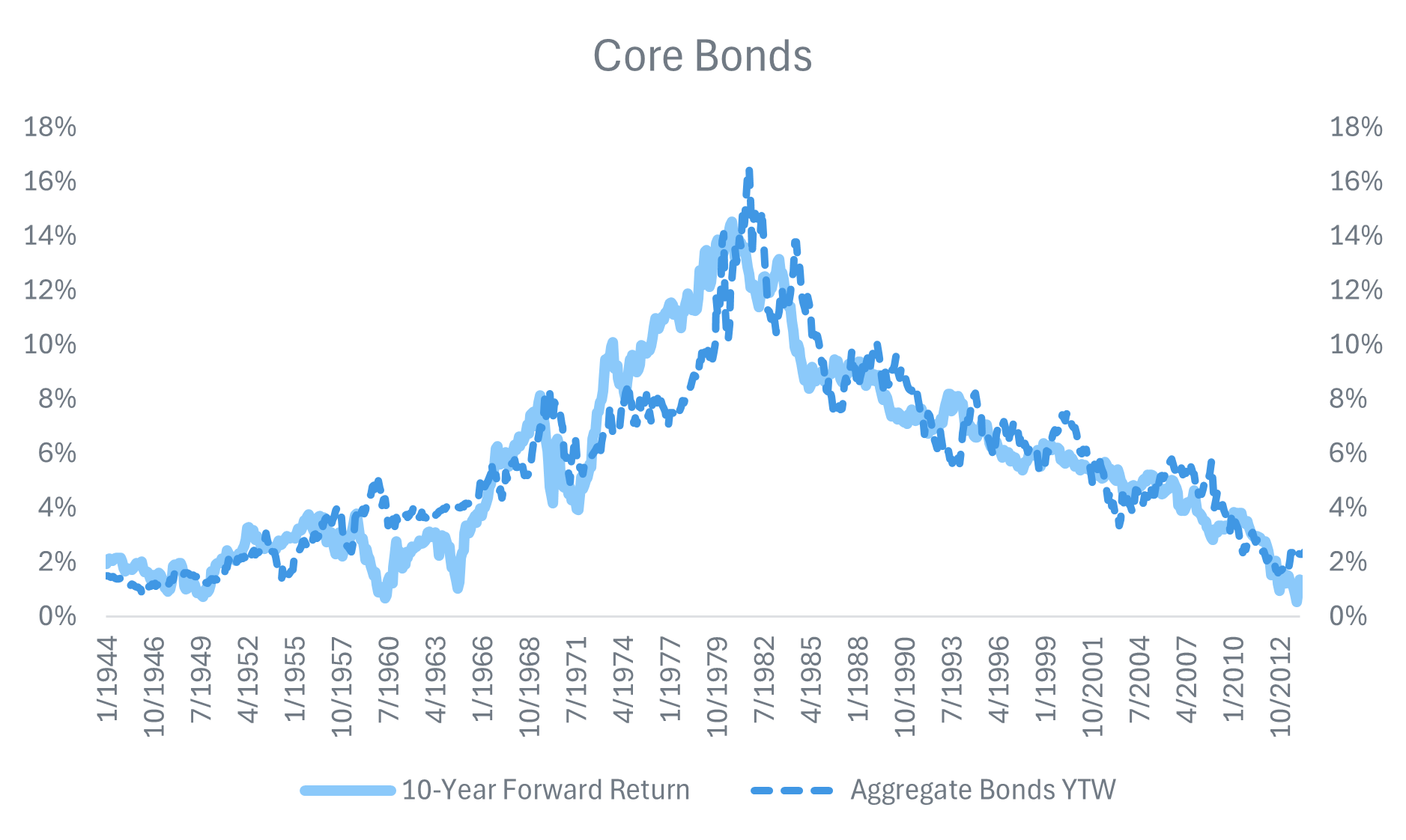

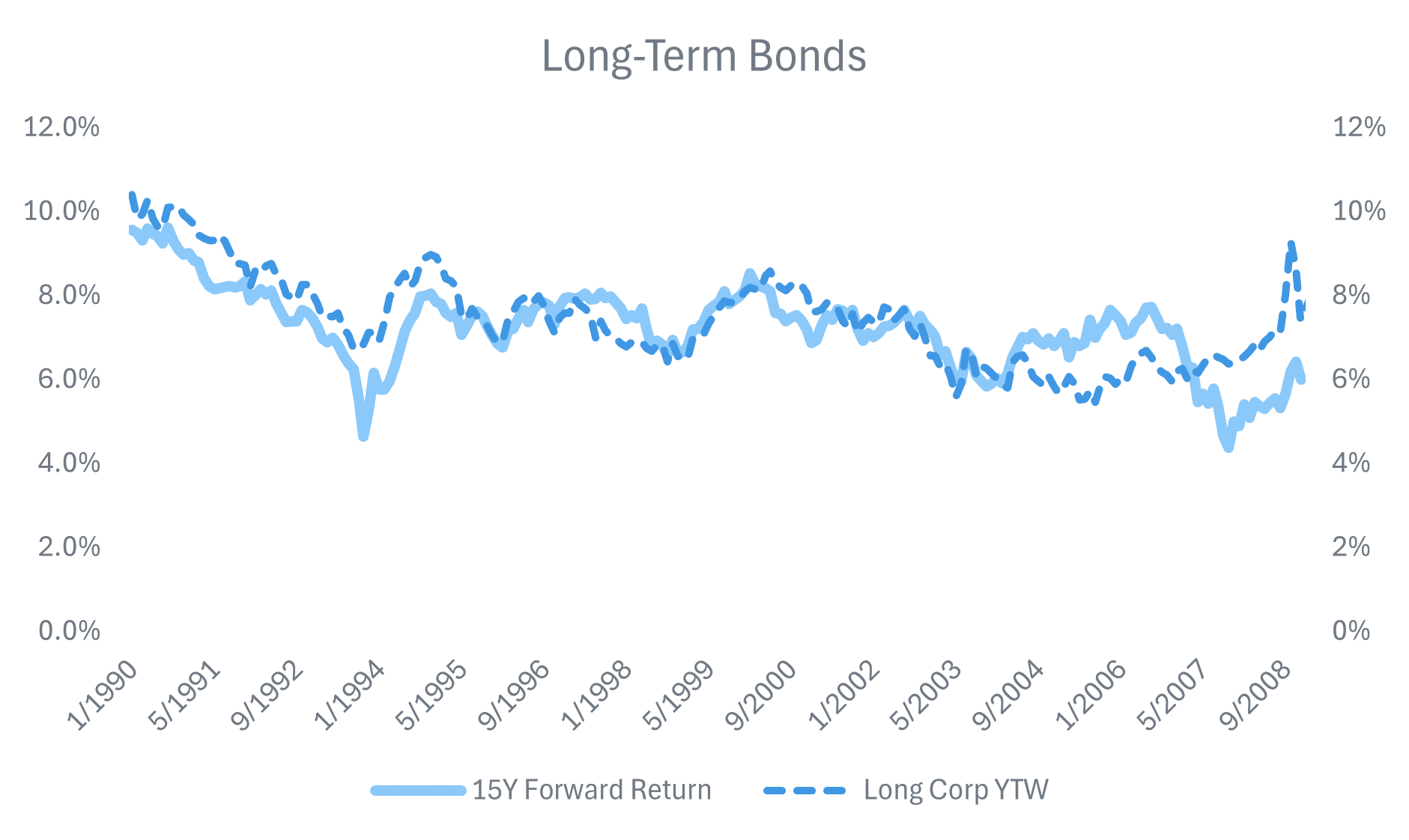

This doesn’t solve the price problem per se. In the near-term interest rate gyrations will still have an impact on fixed income returns, but it gives us the power to comfortably craft investment expectations for high-grade bonds if we constrain the investment horizon to the appropriate tenor, that is the length of time before a bond matures and pays off fully. Short-term bond returns can be confidently forecast over a 1-year timeframe (compare that to the experience of our 30-year treasury investors referenced earlier). Core bonds fit nicely into the standard long-term return expectations window of 10 years. Long-term bonds will require more time to stabilize. So, while market returns over the next few months can bend at the will of Central Bank policy, long-term we can attain some relief from Fed Fatigue.

What does this mean for current bond expectations? It’s fairly straightforward. Over the last 6 months, core bonds have yielded between 4.5% and 5.75%; depending on your entry point. Over the next 10 years you should expect to compound an annualized return in that range. High-grade short-term bonds have traded at slightly higher yields (5.5-6.25%), but the outlook for returns there are only reliable for the next year or so. Long bonds have also seen a wide range of yields, from 5.25% to 6.5% since last September, and will require more time to crystallize. In a nutshell, short-term outcomes will be volatile but long-term outcomes will be stable. The definition of “long term” depends on the duration of the bonds.

Credit: Who’s Credit Worthy and What’s it Worth to You?

The observant reader will have picked up on the modifier “high grade” that slid into the preceding paragraphs. The reason the yield/forward return patterns have fit well in our analysis so far is due in large part to the historical fact that investment grade (IG) bonds rarely default. Rather, credit risk in IG bonds is almost always realized via credit downgrades. Once an issuer slides out of the IG universe it is reclassified as high yield. And high yield bonds tend to default from time to time, leading to credit losses which mar the clean relationship between yield and return for high grade IG bonds.

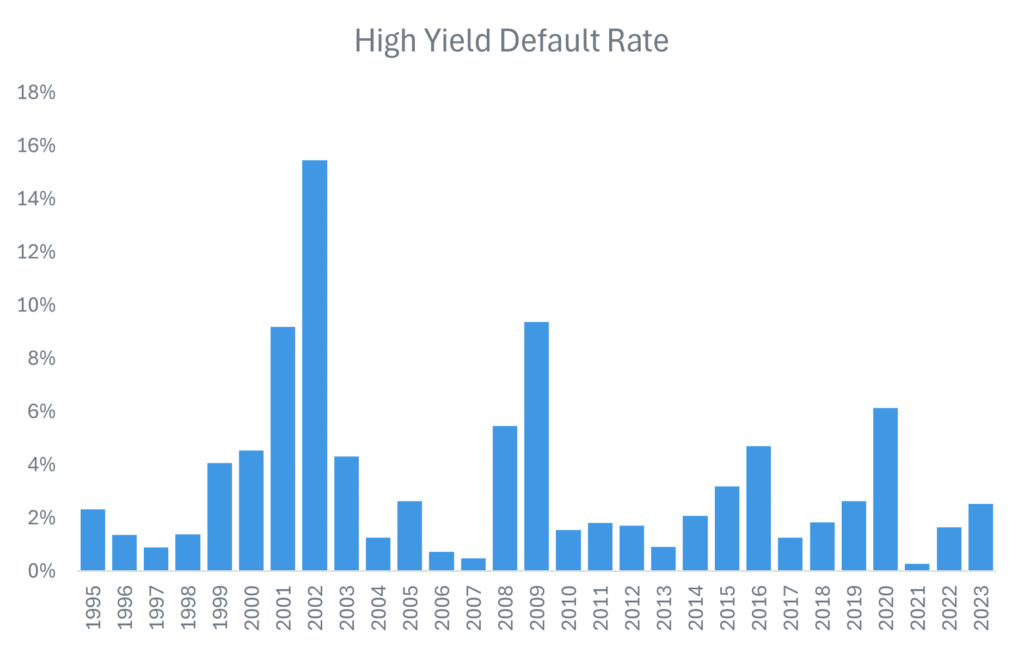

In order to account for default risk in high yield credit we need modify our return outlook and assume two things: the frequency of defaults and the severity of the losses realized in a default situation (remember the bond payers take priority in a default and generally are able to recover some percentage of par value when an issuer cannot repay the full amount owed). This is no simple ask, as illustrated by historical experience. (Note the defaults spiking after the dot-com bubble bust, the Great Financial Crisis and the COVID pandemic.)

Source: UBS

In many years default activity has been quite benign, but when credit markets experience stress, defaults can become elevated. Factors such as economic activity levels and credit availability (or lack thereof) can tip outcomes, and occasionally portend a cascading decline. Recovery rates can also be volatile with industry estimates ranging from 15% to 65% in a given year—the experience is idiosyncratic. That is to say, it’s not just whether there are defaults, but who defaults that determines the outcome.

Credit losses are tricky to forecast but must be accounted for. The high yield bond index was yielding nearly 8% entering 2024, but we cannot expect a return of 8% over the long-term based on this fact alone. For example, if we project a 2% annual default rate and a 50% recovery rate, we need to remove 1% from our forward return (2% of our portfolio will lose half its value on average each year). Depending on the length of your forecast’s investment horizon and the number of adverse credit environments we’ll experience in that time, the results could be better or worse.

Private Credit – A Safe Harbor from the Price Effect?

The new kid on the high yield block is private credit. While private credit is a broad term, encompassing everything from direct loans to companies to asset-backed lending to distressed debt deals, the investment opportunity set is primarily composed of small and mid-sized companies in search of financing unavailable to them in the public markets.

Private credit has two features which have attracted a lot of attention from investors. First, most of these loans are floating rate in nature, meaning the interest paid from the borrowers resets regularly to keep pace with changes in market interest rates. Second, these private loans do not trade in the market—they are held to maturity by the lender. As a result, the need to mark the loans to market and realize price fluctuations almost vanishes. If coupons reset when rates change and no one is buying or selling, there is no impetus for the price of the loans to change; investors are forced into an environment like the ones we illustrated in the buy-and-hold liquid markets examples. And private credit offers yields to investors that are higher than publicly traded high-yield bonds to boot. It’s little wonder that the private debt market has grown to over $1.4 trillion in a relatively short amount of time.

Credit for Borrowers with Few Options

Holding floating rate debt that doesn’t trade has its benefits, but there are drawbacks as well. Floating rate debt is a boon to investors when interest rates are rising, but rising debt service costs put pressure on borrowers, increasing default risk. What type of borrower would need to access capital through private credit channels? After all, public debt through the high-yield or syndicated loan market is cheaper, and typically includes fewer restrictions on the borrower. Most times debt trades on the private market because of necessity: the private market is the only one accessible to the borrowing entity. This can be due to issues such as a low credit rating (or no credit rating), small deal sizes for small enterprises, or some unique aspect or quirk tied to the use of proceeds. In any event, there are unique (sometimes acute) risks associated with the private debt borrowing base.

In the event that there is stress in a particular credit, there is no mechanism to force a loan to be marked down. Rather, that choice lies with the manager. This increases the risk that investors will see an abrupt change when a loan takes a drastic mark down. For example, managers are unlikely to mark a loan from par down to 95, but more likely to wait to take the markdown when the loan needs to be carried at 80, 60, or even 0.

So how do we forecast private credit returns? We have some factors on our side, including the appropriate time horizon, and very little volatility (on paper). But beyond the yield advantage over high-yield counterparts are loans that are typically lower quality, and more susceptible to distress and default, with little to no historical data on which to pin our assumptions. More return, more risk, less volatility. Modeler beware.

Investing in Fixed Income Abroad

Beyond our borders the fixed income landscape offers many of the same choices: government debt, corporate bonds (both investment grade and high yield), private and publicly traded loans. But there is an additional choice to make when allocating to non-U.S. bonds; and that is currency. As a consequence of the dollar’s prolonged rule as the world’s reserve currency, many foreign fixed income investments are denominated in U.S. dollars, while others are offered in the local currency of the issuer (other non-European/non-Japanese foreign bonds may be denominated in Euro or Yen terms but we exclude those from our conversation).

Foreign bonds denominated in U.S. dollars and local currency bonds price at differing yields, due in large part to the means of accessing funds for repayment. A dollar borrower must come up with dollars to repay interest and principal. For a foreign corporation exporting goods to America, sourcing dollars may not be all that difficult. For other borrowers, producing dollars can be more complicated. Sovereign issuers rely on currency reserves to repay debts, and currency reserves play multiple roles in a country’s monetary policy. A local currency issuer has no such trouble, a sovereign borrower in particular can always print more local currency to pay what’s owed. A dollar-based lender receiving local currency payments is then tasked with converting that payment back to U.S. dollars.

The currency dynamic illustrates the relative risks investors take in lending to foreign borrowers. USD bonds tend to trade at lower yields since the currency risk is borne by the borrower. The risk that the borrower cannot come up with the funds is baked into the credit spread. While a developed country or a multi-national conglomerate based in Europe might be considered lower risk, greater attention is focused on the credit fundamentals and national balance sheets of developing countries. For local currency bonds, the borrower absorbs currency fluctuations, generally resulting in more volatility. A weakening currency will eat into returns, while a strengthening currency will give investors an added boost.

Modeling the nuances of investing in fixed income outside of the U.S. is a challenging task. Taking on currency volatility is an interesting dilemma in the sense that it is broadly seen as an “uncompensated risk,” or additional risk for which there is no related return. Default risk can be priced but it is important to recognize that the rule of law governing default proceedings varies (sometimes drastically) once investors extend their portfolios internationally. Sovereign issuers in default wield the power to rewrite laws and policy at the expense of creditors. They are incentivized to “play nice” only to the extent that there will be a need to access capital markets again in the future. Historical recovery rates, on average, have been in line with U.S. high yield.

The Cure for Short Term Fed Fatigue: A Long-Term View on Investment Grade U.S. Bonds

Investing in fixed income presents many choices and opportunities for investors, and a number of challenges for modelers. Academics have made valiant attempts to capture the movement of rates and the shape of the yield curve in models of varying complexity, but so far, the real world has been too crafty to be mimicked by a mathematical formula. (To wit, modelers 20 years ago would have considered negative interest rates, an economic oxymoron, to be a defect in a model, yet many sovereign rates were negative for a good portion of the 2010s). But for long-term investors, the relationship between yield and forward return offers respite for investment grade U.S. bonds, and a firm jumping-off-point for other corners of the market.

Highland Consulting Associates, Inc. was founded in 1993 with the conviction that companies and individuals could be better served with integrity, impartiality, and stewardship. Today, Highland is 100% owned by a team of owner-associates galvanized around this promise: As your Investor Advocates®, we are Client First. Every Opportunity. Every Interaction.

Highland Consulting Associates, Inc. is a registered investment adviser. Information presented is for educational purposes only and is not intended to make an offer of solicitation for the sale or purchase of specific securities, investments, or investment strategies. Investments involve risk and unless otherwise stated, are not guaranteed. Be sure to first consult with a qualified financial adviser and/or tax professional before implementing any strategy discussed herein. Past performance is not indicative of future performance.